Candomblé is an Afro-American religious tradition. Its first temple was founded in Salvador da Bahia – the capital of the Brazilian state of Bahia – in the early 1800s.

Candomblé is primarily practiced in Brazil, but also enjoy a fairly large following in several other Latin American countries, including Venezuela, Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina. Practitioners of candomblé collectively call themselves povo do santo.

Candomblé is an oral tradition and doesn’t have holy scriptures. Only recently have practitioners and scholars begun to write down various aspects of the belief system and its rituals.

Polytheism

Povo do santo believe in a supreme creator called Oludumaré.

Oludumaré is served by a selection of lower deities; the orishas.

Every person who practices candomblé have their own tutelary orisha. This orisha will both act as a protector and influence your destiny.

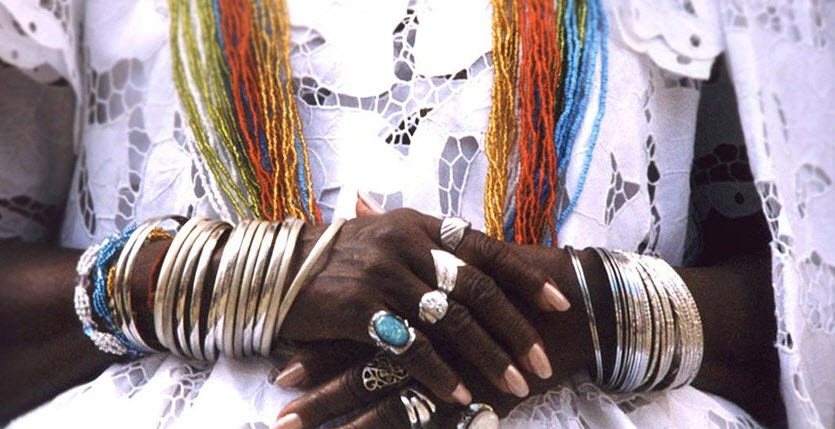

With the help of ceremonial music and dancing, practitioners can open themselves up to be possessed by orishas. As a part of such a ritual, the practitioner will make offerings from the animal kingdom, the plant kingdom and the mineral kingdom.

The name

The name candomblé means “dance in the honor of the gods”.

Until the 1800s, the religion was more commonly referred to as batugue.

Both candomblé and batugue are believed by scholars to be words derived from a language belonging to the Bantu-family of languages.

History

Candomblé developed in Brazil among slaves, when Brazil was still a part of the Portuguese Empire. It is widely regarded as a creolization of traditional Yoruba, Fon and Bantu beliefs from West Africa. Also, candomblé absorbed elements from local Native American traditions and from Roman Catholicism.

The Catholic church and the Portuguese Empire were both eager to convert African slaves and Native Americans to Catholicism, and did so with varying success. Many slaves outwardly participated in the rituals of the catholic church, including baptism, but secretly kept their beliefs in their own deities and ancestor spirits, and also passed this knowledge – including knowledge about various rituals – along to the next generations.

Catholic fraternities were founded were slaves ostensibly met to exercise and deepen their Christian faith. In reality, these fraternities often turned into an opportunity to engage in Candomblé worship. On certain holy days, Candomblé feasts were held, under the cover of Catholicism.

Catholic saints and orishas

For many adherents of Candomblé, the Catholic veneration of saints was seen as strongly resembling their own veneration of various orishas. Thus, strong ties were formed between orishas and the saints. These ties even extended to very practical aspects of worship, such as hiding sacred Candomblé symbols inside figurines depicting Catholic saints.

Bantu and Brazil’s indigenous peoples

The traditional Bantu faith includes ancestor worship. Through interaction with some of Brazil’s indigenous people, slaves of Bantu origin came into contact with a similar system of ancestor worship, and this is believed to have helped preserve and strengthen the Bantu ancestor worship in Brazil.

Islam connection

Quite a few of the slaves from West Africa were Muslims or had been acculturated with Muslim traditions in Africa, and this also had an impact on the developing Candomblé.

Persecution

The Catholic Church strongly condemned the candomblé (batugue) and those who were discovered to be followers of the faith were violently persecuted. The Portuguese Empire, which had strong ties to the Catholic Church, launched government-led public campaigns against the povo do santo and also utilized their police force and justice system to punish practitioners.

Surge in popularity

In the 1970s, a Brazilian law stipulating that public religious ceremonies required police permission was repealed. This largely ended the legal persecution of povo do santo and the faith surged in popularity when it could finally be practiced more openly.